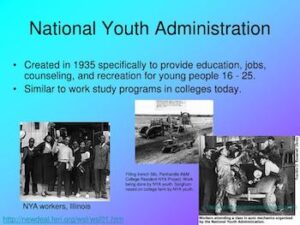

National Youth Administration

*On this date in 1935, we celebrate the creation of the National Youth Administration (NYA).

Franklin Roosevelt signed the executive order establishing the NYA, a New Deal program explicitly designed to address the problem of unemployment among (then) Depression-era youth. The number of unemployed youths in the 1930s drew attention to several fears adults had for society.

Conservatives saw disgruntled young people as a fertile ground for revolutionary politics, while liberals mourned the disillusionment and apathy spreading among American youth. Educators feared that without some financial aid, colleges would suffer irreversible damage. Eleanor Roosevelt and others worried that long-term unemployment and near-poverty would undermine young Americans' faith in democracy.

She told The New York Times, "I live in real terror when I think we may be losing this generation. We have got to bring these young people into the active life of the community and make them feel that they are necessary." Roosevelt, who worked closely with educators and relief officials, pushed her husband, Franklin Roosevelt, to address this problem. The NYA sought to cope with this problem in two ways.

First, the administration provided grants to high school and college students in exchange for work. This allowed young people to continue studying while simultaneously preventing the pool of unemployed youth from growing larger. Second, for those young people who were both unemployed and not in school, the NYA aimed to combine economic relief with on-the-job training in federally funded work projects designed to provide youth with marketable skills for the future. The latter was, by far, the more challenging of the NYA's tasks, and by 1937, the project had provoked some criticism for failing to provide adequate funding for job training.

As a result, the administration shifted its emphasis to skills development in late 1937, the same year it launched a special assistance program for blacks. Mary Mcleod Bethune was appointed Director of the Division of Negro Affairs for the National Youth Administration. She was the first Black woman to receive a presidential appointment and was the highest-ranking Black woman in an administrative position in President Theodore Roosevelt's administration. This branch partnered with universities, politicians, and business owners to help prepare black women for the workforce. Thousands of black girls and young women participate in programs organized by Bethune, earning money through job training and improving their communities by supporting essential industries such as healthcare and education.

An estimated 300,000 young Black women participated in this program. The President's wife became the NYA's most public champion, often visiting NYA centers and praising its activities in her column. She took such joy in the program that when she discussed it in her autobiography, she took credit for its creation. She told her readers, "One of the ideas I agreed to present to Franklin was setting up a national youth administration. It was one of the occasions on which I was very proud that the right thing was done regardless of political consequences."

The NYA's priorities shifted again in 1939 as unemployment began to wane and war gradually approached. The NYA emphasized skills training in defense-related industries for the next four years. Despite the NYA's success, as wartime spending increased, Congress refused to continue funding the program and abolished the NYA in 1943.