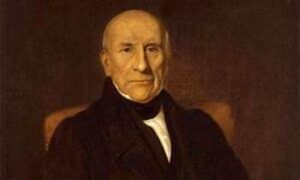

William Gladstone

*William Gladstone was born on this date in 1809. He was a white British statesman, slave owner, and politician.

Born in Liverpool, William Ewart Gladstone was of Scottish ancestry. He was the fourth son of the wealthy enslaver John Gladstone and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson. In 1814, young "Willy" visited Scotland for the first time, as he and his brother John traveled with their father.

William Gladstone was educated from 1816 to 1821 at the vicarage of St. Thomas' Church at Seaforth. In 1821, he attended Eton College. In December 1831, he achieved a double first-class degree. Gladstone was President of the Oxford Union, where he was an orator, which followed him into the House of Commons. At university, Gladstone denounced Whig's proposals for parliamentary reform in a famous debate at the Oxford Union in May 1831. On the second day of the three-day debate on the Whig Reform Bill, Gladstone moved the motion: 'That the Ministry has unwisely introduced, and most unscrupulously forwarded, a measure which threatens not only to change the form of our Government but ultimately to break up the very foundations of social order, as well as materially to forward the views of those who are pursuing the project throughout the civilized world.'

Gladstone's early attitude towards slavery came from his father, one of the largest enslavers in the British Empire. In 1831, when the Oxford Union considered a motion in favor of the immediate emancipation of the enslaved people in the West Indies, Gladstone moved an amendment in favor of gradual manumission along with better protection for the personal and civil rights of the slaves and better provision for their Christian education. Gladstone wanted gradual rather than immediate emancipation and proposed that slaves should serve a period of apprenticeship after being freed.

He also opposed the international slave trade (which lowered the value of the slaves the father already owned). The antislavery movement demanded the immediate abolition of slavery. In 1832, Gladstone opposed this and said that emancipation should come after moral emancipation through adopting an education system and inculcating "honest and industrious habits" among the enslaved people. Then "with the utmost speed that prudence will permit, we shall arrive at that exceedingly desired consummation, the utter extinction of slavery." His early Parliamentary speeches followed a similar line. In June 1833, Gladstone concluded his speech on the 'slavery question' by declaring that though he had dwelt on "the dark side" of the issue, he looked forward to "a safe and gradual emancipation."

In 1834, slavery was abolished across the British Empire, and owners were paid full value for their slaves by the government. Gladstone helped his father obtain £106,769 in official reimbursement by the government for the 508 slaves he owned across nine plantations in the Caribbean. In later years, Gladstone's attitude towards slavery became more critical as his father's influence over his politics diminished.

Shortly after the outbreak of the American Civil War, Gladstone wrote to his friend, the Duchess of Sutherland, that "the principle announced by the vice-president of the South...which asserts the superiority of the white man, and in addition to that founds on it his right to hold the black in slavery, I think that principle detestable, and I am whole with the opponents of it" but that he felt that the North was wrong to try to restore the Union by military force, which he believed would fail. Palmerston's government adopted a position of British neutrality throughout the war while declining to recognize the independence of the Confederacy.

In October 1862, Gladstone made a speech in Newcastle in which he said that Jefferson Davis and the other Confederate leaders had "made a nation," that the Confederacy seemed certain to succeed in asserting its independence from the North, and that the time might come when it would be the duty of the European powers to "offer friendly aid in compromising the quarrel."

The speech caused consternation on both sides of the Atlantic and led to speculation that Britain might be about to recognize the Confederacy." He clarified in the press that his comments in Newcastle were not to signal a change in Government policy but to express his belief that the North's efforts to defeat the South would fail due to the strength of Southern resistance. In a memorandum to the Cabinet later that month, Gladstone wrote that, although he believed the Confederacy would probably win the war, it was "seriously tainted by its connection with slavery" and argued that the European powers should use their influence on the South to affect the "mitigation or removal of slavery."

Looking back late in life, Gladstone named the abolition of slavery as one of ten outstanding achievements of the past sixty years where the masses had been right and the upper classes had been wrong. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-consecutive terms (the most of any British prime minister) beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894. He also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer four times for over 12 years. He formed his last government in 1892 at the age of 82. William Gladstone left office in March 1894, aged 84, as both the oldest person to serve as Prime Minister and the only prime minister to have served four non-consecutive terms.

He left Parliament in 1895 and died three years later, on May 19, 1898. Gladstone was known affectionately by his supporters as "The People's William" or the "G.O.M." ("Grand Old Man" or, to political rivals, "God's Only Mistake"). Historians often rank Gladstone as one of the greatest prime ministers in British history.