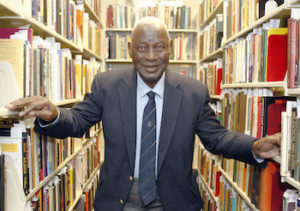

Dr. Charles Blockson

*Charles Blockson was born on this date in 1933. He was a Black educator, historian, and author.

Charles LeRoy Blockson was born in Norristown, PA, the son of Charles E. Blockson and Annie Parker Blockson. As a child, he contracted pneumonia and scarlet fever, wasn't expected to live, and developed a lisp. In his youth, he helped his mother with household chores and worked with his father, who owned a painting and plastering business, during the summer. Despite his early illness, he became a physically strong child and participated in sports at school in his community.

Blockson loved books early on and learned about Black history from listening to his grandfather sing. Blockson's great-grandfather, James Blockson, had been a slave in Delaware and had escaped into Pennsylvania on the Underground Railroad. "One Sunday afternoon, I asked him what he was singing about. He said he was singing about the Underground Railroad." "Our textbooks in those days said that all the slaves were happy on the plantations," Blockson noted in Safe Harbor. "But I said to myself as I started to get into it, 'If the enslaved people were happy, why did they run away?'"

Blockson later recalled another childhood experience that led to his zeal to document Black contributions to American history. As a young boy, he asked his white teacher about the importance of African Americans in building the nation. She told him, "Negroes have no history," quoted Frank Whelan in the Morning Call. "They were born to serve white people." Fifty years later, the teacher phoned Blockson to apologize. "Charles, you have taught us all something about ourselves and our place in history."

Blockson excelled in football and track at Norristown High School, where he became Pennsylvania's shot put and discus champion from 1950 to 1952. Because of his athletic skills, 60 colleges offered him scholarships. He chose Pennsylvania State University, where he majored in physical education and played fullback with Roosevelt Grier and Lenny Moore. Later, he turned down a chance to play professional football with the New York Giants.

Blockson served in the Army for two years after college, and following his discharge, he started a janitorial service. He married Elizabeth Parker, and they have one daughter, Noelle. In 1972, Blockson became an adviser for human relations and cultural affairs at the Norristown Area High School. He taught African American history, recruited faculty, and helped to diffuse sensitive race issues. He helped found the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum in Philadelphia in 1976. Blockson also continued to devote time to building his collection of African American history books and tracing his family's genealogy.

In 1977, he published his first book, Black Genealogy. In 1984, Blockson donated his private book collection to the Special Collection Department of Temple University Libraries. The collection has over 150,000 items, including books, photographs, drawings, sheet music, posters, and broadsides, and was once housed in Blockson's basement. The Blockson Library collection covers and documents four hundred years of African American experience. It includes African Bibles, correspondence with Haitian revolutionaries, narratives by Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, and first editions of writings by Phyllis Wheatley and W.E.B. Du Bois. The collection also proved essential to founding a doctorate program for African American studies at Temple University. In 1987, Blockson published The Underground Railroad: First-Person Narratives of Escapes to Freedom in the North. He has also championed the preservation of Underground Railroad history.

His noted awards include the Alumni Fellow Award, Pennsylvania State University, 1979; Lifetime Achievement Award, Before Columbus Foundation, 1987; Whitney Young Human Relations Award, Philadelphia Urban League, 1991. Charles Blockson critiqued the United States Park Service's plans to construct a nine-million dollar pavilion to house the Liberty Bell. The problem with the site on which the pavilion is being constructed was that in 2001, it was discovered that George Washington housed his slaves on the site when he lived in Philadelphia during the 1790s. Washington was president at the time, and slavery was illegal in Pennsylvania. "Slavery was about money, and today tourism is about money," Blockson told Linn Washington, Jr. in the Philadelphia Tribune. "Are they going to tell the truth to tourists? There should be no more lies. Maybe the crack in the Bell is for hypocrisy!"

Blockson has been a vocal critic of efforts to obscure and soft-sell African American history. In 2002, he spoke out against the Insurance Company of North America, which denied that it profited by insuring slave ships in the 18th and 19th centuries. "Philadelphia insured more sailing vessels dealing in slavery than any other port besides Boston," he told Joseph N. DiStefano in the Philadelphia Inquirer. "They were damn well involved."

In 2017, Blockson was the 96th recipient of the Philadelphia Award. Charles Blockson died on June 14, 2023, at 89.

Voices That Guide Us Interview,

African American Registry®, 2012