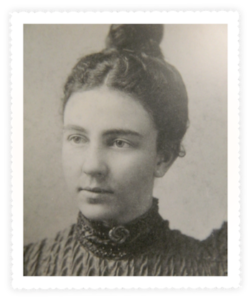

Adrienne Herndon

*Adrienne Herndon was born on this date in 1869. She was a Black actress, educator, and designer.

Born in Savannah, Georgia, Adrienne McNeil was the daughter of light-skinned, slave-born house servants with considerable white ancestry. From her childhood through her drama studies in Boston and New York, Adrienne held on to this dream of a career on the legitimate theater stage. The harsh realities of race and gender in America, however, tragically doomed the realization of this dream. There was no place for her on the American theater stage except for vaudeville, minstrelsy, and all-Black dramatic productions. She identified herself as a Creole. She neither admitted to nor denied her race.

Adrienne McNeil married Alonzo Herndon in 1894, the first Black millionaire in Atlanta. In 1897, they had a son, Norris Bumstead Herndon. Ahead of her time and outside her assigned place, Adrienne Herndon achieved acclaim in education, drama, and architecture in turn-of-the-century Atlanta. She graduated from Atlanta University, a normal school in preparation for teaching. She received degrees from the Boston School of Expression and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York.

Passing for white, she made her debut in Boston. Under Anne Du Bignon's stage name, Herndon performed in Steinert Hall, reciting the twenty-two parts of Shakespeare's Anthony and Cleopatra. Having thoroughly promoted her debut through advertisements and well-placed references, she garnered the attention of more than ten Boston-area newspapers. But only one more engagement came: a reading in Bellow Falls, Vermont, miles from Boston.

Placing her dream on hold, Adrienne threw herself into her work as head of the Department of Drama and Elocution at Atlanta University. She brought Shakespeare to the South, presenting the University's first Shakespearean production; Herndon directed the University's theater offerings and gave Atlanta's Black community access to drama with professional stage sets and costumes. Moreover, she opened the university community to the American theater world. They hosted the William Gillette Theater Company of New York in a performance of Sherlock Holmes in the Adventure of the Second Stain. She engaged others at the University in her work. W. E. B. Du Bois, her colleague on the faculty, served as the stage manager for the Gillette production.

Herndon experienced the frustrations of gender and the exclusions of race. Before their marriage, Alonzo Herndon promised to allow Adrienne to pursue her studies in drama. He probably had no idea, however, how demanding of time and resources that pursuit would be. Nor would he have fully appreciated at the time that any serious career on the stage would mean extended absences from home. Ironically, the exclusion from the theater returned Adrienne to her home and family full-time.

In one last desperate grab for the stage, she studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York. She was furthering her drama studies and escaping Atlanta, a city that had just undergone the worst racial violence in Georgia. In fear and disgust, Adrienne moved her young son, Norris, to Philadelphia to live with relatives and enrolled at the Academy, which was not far away in New York, leaving her husband in Atlanta. While racism in the North did not generally reflect the violent extremes of racism in the South, it was no less destructive.

She returned to Atlanta with her son and became absorbed in a domestic project that would be one of her most significant contributions. Nearly two years after the Atlanta Riot, the Herndons began constructing the new house they had been planning for some time. With Adrienne as an architect and Alonzo as builder/contractor, a two-story Beaux-Arts Classical house was erected adjacent to Atlanta University.

Within three months of its completion, Adrienne Herndon died of Addison's disease in 1910, and her struggles with race and gender were only partially resolved. Denied the American stage, she developed one in her neighborhood. Frustrated by her efforts to be an artist outside of the home, she made her home the focus of her artistic talent, designing a landmark to memorialize her work and that of her family. Their Atlanta mansion, Herndon Home, which she designed, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2000.