Dovey Johnson Roundtree

*Dovey Johnson Roundtree was born on this date in 1914. She was a Black teacher, lawyer, military administrator, and minister.

From Charlotte, NC, Dovey Mae Johnson was the second of four daughters of James Eliot Johnson, a printer, and Lela (Bryant) Johnson, a domestic. Her father died in the influenza epidemic of 1919, and she, her mother, and sisters were taken in by her maternal grandparents, the Rev. Clyde L. Graham, a minister in the A.M.E. Zion Church, and Rachel Bryant Graham.

Reared in her grandfather’s shotgun-shack parsonage in one of Charlotte’s Black districts, she was profoundly influenced by her grandmother, who, with a third-grade education, was a revered community member. Born not long after the American Civil War ended, Graham had weathered the death of her first husband at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. She lived with feet so badly crippled that she was in constant pain: When she was a teenager, she had thwarted a white man’s attempts to rape her by running. Enraged, he stomped her feet, shattering them to ensure she would never run again.

Roundtree recalled huddling beneath her grandmother’s kitchen table with her mother and sisters as Klansmen raged through their community on horseback. Graham stood guard on the front porch, wielding her household broom as the hooded riders rode by. It was an index of her grandmother’s formidable appearance, Roundtree said, that it did not occur to her until years later how slender an armament a broom was.

Encouraged by her grandmother’s friend, Mary McLeod Bethune, young Johnson set her sights on becoming a doctor. She enrolled at Spelman College and later wrote, “I was in my own way an outsider, a poor working student in a sea of black privilege.” To remain in school, she held three simultaneous jobs, including domestic work for a white family.

She graduated in 1938 with a double major in English and biology. It was Bethune to whom Roundtree turned in 1941, as World War II's threat generated unprecedented jobs for Blacks in the country's "defense preparedness" program. Resigning from the South Carolina teaching position she had taken up on college graduation in 1938, she sought Bethune in Washington, D.C., for assistance in obtaining employment in the burgeoning defense industry. Bethune immediately tapped her for the select group of 40 Black women to become the first to train as officers in the newly created Women's Army Auxiliary Corps.

Roundtree publicly challenged the racial discrimination in the rigidly segregated Army even as she recruited other black women for the WAAC on assignment in the Deep South. Traveling in uniform in the winter of 1943 without Army protection, she was evicted from a Miami bus and forced, under threat of arrest, to yield her seat to a white Marine. She continued recruiting Black women into the Corps in such numbers that, although the women served in segregated units, the groundwork was laid for an interracial Army. Following World War II and a nine-month assignment with the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), Johnson rekindled a romance with William Roundtree that had started at Spelman College. They married on Christmas Eve, 1946, but lasted less than a year.

Roundtree entered the American civil rights field in October 1945 in a nine-month postwar assignment with Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph was staging a national campaign to make the wartime Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) a permanent entity. Her FEPC involvement brought her into contact with lawyer Pauli Murray, a passionate civil rights activist and legal academic who later founded the National Organization for Women. Inspired by Murray, Roundtree enrolled at Howard University School of Law in the fall of 1947, one of only five women in her class. From 1947 to 1950, she immersed herself in the assault on school segregation by Thurgood Marshall, James Nabrit Jr., and George E. C. Hayes, which in 1954 culminated in the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision. In 1952, Roundtree, along with her partner and mentor Julius Winfield Robertson, during her first year of legal practice, took on a bus desegregation case that would make legal history: Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company (1955).

The Keys case challenged the right of a private bus carrier to impose its Jim Crow laws on black passengers traveling across state lines. When the US District Court dismissed the matter for the District of Columbia on jurisdictional grounds, Roundtree and Robertson took their complaint to the Interstate Commerce Commission, the federal administrative body enforcing the Interstate Commerce Act. Turned down by the Commission on their first pass, they filed exceptions, arguing that the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board, handed down in May of that same year, also delegitimized segregation in public education and public transportation. On November 7, 1955, in a historic ruling in which the ICC departed from its long history of adherence to the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) ruling, the Commission banned separate but equal for the first time in interstate bus travel.

Roundtree and Robertson represented Black clients in civil and criminal matters in the segregated courtrooms of Washington, DC. During the 1950s, black lawyers had to leave the courthouses to use the bathrooms. Black clients were routinely referred to white attorneys to maximize their chances in court; Roundtree and Robertson broke with tradition. They pressed the cases of Black clients before white judges and juries and prevailed, winning sizable recoveries in accident and negligence cases. Their 1957 victory in a negligence case against a Washington, DC psychiatric facility, which resulted in the maximum recovery allowable under the Federal Tort Claims Act at that time, was widely regarded as a turning point not only for Black clients in the Nation's Capital but for Black attorneys as well.

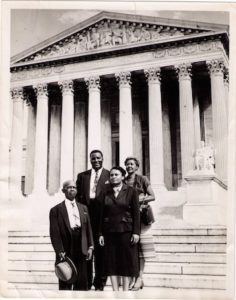

The Keys case lay dormant for six years, blunted mainly by the ICC commissioner who had dissented from the majority opinion, South Carolina Democrat J. Monroe Johnson. On May 29, 1961, responding to the protests of civil rights leaders, Robert Kennedy issued a Justice Department petition in which he cited Keys and the companion NAACP train case, along with the 1960 Supreme Court Boynton v. Virginia ruling, and called upon the ICC to enforce the ruling it had handed down itself in 1955. Under pressure from the Attorney General, the Commission finally acted upon its rulings and, in September 1961, put a permanent end to segregation in travel across state lines. (Robertson and Roundtree are pictured below.)

The death of Julius Robertson from a heart attack in November 1961 marked a turning point for Roundtree, who, as a black woman, found herself a sole practitioner in a legal community still dominated by men. In 1962, she broke another barrier with her nomination for membership to the all-white Women's Bar Association of the District of Columbia as its first Black member. Sustained by her ordination into the African Methodist Episcopal Church ministry on November 30, 1961, Roundtree went on to build a thriving law practice, working as a sole practitioner for nine years before founding a second law firm, Roundtree Knox Hunter and Parker, in 1970.

It was Roundtree's successful defense of a Black laborer accused of the 1964 murder of alleged John Kennedy mistress Mary Pinchot Meyer that solidified her reputation in the Washington, D.C., legal community. For a fee of one dollar, Roundtree took on the defense of Ray Crump, Jr., accused of the execution-style shooting of Meyer as she took her daily walk along the C & O Canal. Crump, who had been found by police wandering along the towpath near the crime scene, was arrested on the word of an eyewitness who claimed Crump resembled the Black man he had seen standing over Meyer's body moments after the murder. He had then been indicted without a preliminary hearing.

Convinced that Crump's limited mental capacity rendered him incapable of perpetrating a murder of such stealth and meticulousness, Roundtree took on the United States government in a July 1965 trial in which the notoriety of the victim drew record crowds of lawyers, law students, and reporters to the United States District Court.

In the summer of 1965, the country seethed with racial tension amid the surging civil rights movement. Federal prosecutors had amassed circumstantial evidence, including 27 witnesses and more than 50 exhibits. By contrast, Roundtree presented just three witnesses and a single exhibit to the jury, which comprised men and women, Blacks and whites. Her closing argument was only 20 minutes long. On July 30, 1965, the jury had deliberated. The court clerk handed the verdict slip to the judge, Howard F. Corcoran. “Members of the jury,” Judge Corcoran said. “We have your verdict, which states that you find the defendant, Ray Crump Jr., not guilty.” Her defense, which hinged partly on two forensic masterstrokes, made her reputation as a litigator of acuity, concision, and steel who could win even the most hopeless trials. Plus, this is in a case in a courthouse where she was not allowed to use the law library, cafeteria, or restroom.

In 2009, Michelle Obama said, “As an Army veteran, lawyer, and minister, Ms. Roundtree set a new path for the many women who have followed her and proved once again that the vision and perseverance of a single individual can help to turn the tides of history.” Yet for all her perseverance and all her prowess, Ms. Roundtree remained, by temperament, choice, and political circumstance, comparatively unknown. “One has to start with the fact, and I think it’s an acknowledged fact, that the civil rights movement was notoriously sexist,”

Katie McCabe, the co-author of Ms. Roundtree’s memoir, Justice Older Than the Law, said in 2016. “There were many men who did not appreciate being ground up into hamburger meat by Dovey Roundtree. There are many, many white lawyers in Washington who were humiliated by having been beaten by a Black woman. And I think that played out in a number of ways. And one of those ways has been a diminution in the recognition that I think her accomplishments merit.” Dovey Johnson Roundtree died in Charlotte, N.C., on May 21, 2018.