*The American Great Migration is affirmed on this date in 1916. Sometimes referred to as the Great Northward Migration or the Black Migration, this event unfolded in two distinct chapters.

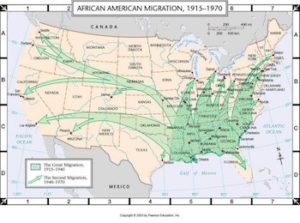

The first Great Migration (1916–1940) saw approximately 1.6 million people move from predominantly rural areas in the South to northern industrial cities. The Second Great Migration (1940–1970) began after the Great Depression and brought at least 5 million people, including many town residents with urban skills, to the North and West.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, less than eight percent of African Americans lived in the Northeastern or Midwestern United States. This began to change over the next decade; by 1880, migration to Kansas was underway. The U.S. Senate ordered an investigation into it. In 1900, approximately 90 percent of African Americans still resided in Southern states. African Americans moved as individuals or small family groups. There was no government assistance, but northern industries, such as railroads, meatpacking, and stockyards, often covered the costs of transportation and relocation.

In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual Hampton Negro Conference in Virginia, said that "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage-earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South. There seems to be an apparent effort throughout the North, especially in the cities, to debar the colored worker from all the avenues of higher remunerative labor, which makes it more difficult to improve his economic condition even than in the South."

Between 1910 and 1930, the Black population in Northern states increased by approximately forty percent due to migration, primarily to major cities. The cities of Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, Baltimore, and New York City had some of the most significant increases in the early part of the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of Blacks were recruited for industrial jobs, such as positions related to the expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Because changes were concentrated in cities, attracting millions of new or recent white-European immigrants, tensions rose as people competed for work and scarce housing. Tensions were often most severe between ethnic Irish, defending their recently gained positions and territory, and recent immigrants and Blacks.

In the late summer and autumn of 1917, racial tensions became more violent and were known as the Red Summer. This period was defined by violence and prolonged rioting between Blacks and whites in central United States cities. The reasons for this violence vary. Cities that were affected by the violence included Washington, D.C., Chicago, Omaha, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Elaine, Arkansas, a small rural town 70 miles southwest of Memphis. The race riots peaked in Chicago, for the most violence and death occurred there during the riots. The authors of The Negro in Chicago, a study of race relations and a race riot, an official report from 1922 on race relations in Chicago, concluded that many factors led to the violent outbursts in Chicago. Principally, many Blacks were assuming the jobs of white men who went to fight in World War I.

As the war ended in 1918, many men returned home to find out their jobs had been taken by Black men willing to work for far less. By the time the rioting and violence had subsided in the 1919 Chicago Riot, 38 people had lost their lives, with 500 more injured. Additionally, $250,000 worth of property was destroyed, and over a thousand persons were left homeless. In other cities nationwide, many more had been affected by the violence of the Red Summer. The Red Summer enlightened many about the growing racial tension in America. The violence in these major cities prefigured the Harlem Renaissance that was to follow in the 1920s. Racial violence reoccurred in Chicago in the 1940s, in Detroit, and in other cities in the Northeast as racial tensions over housing and employment discrimination grew.

Historically, in every U.S. Census before 1910, more than 90% of African Americans lived in the American South. In 1900, only one-fifth of African Americans living in the South lived in urban areas. By the end of the Great Migration, just over 50% of African Americans remained in the South, while a little less than 50% lived in the North and West, and African Americans had become highly urbanized. By 1960, half of the Black population still living in the South resided in urban areas, and by 1970, more than 80% of African Americans nationwide lived in cities. Since the mid-20th century American Civil Rights Movement, there has been less rapid reverse migration.

The New Great Migration gradually increased African American migration to the South, primarily to states and cities with the best economic opportunities. The reasons include the financial difficulties of towns in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States, the growth of jobs in the "New South" and its lower cost of living, family and kinship ties, and improved racial relations.