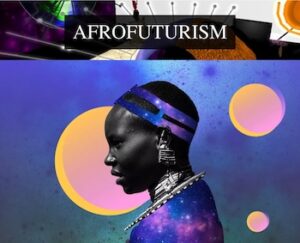

Black history and Afro futurism

*Black history and Afrofuturism are affirmed on this date in 1993. Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science, and history that explores the intersection of the African diaspora culture with science and technology.

Through techno culture and hypothetical fiction, it includes a range of media and artists with a shared interest in envisioning Black futures. While Afrofuturism is most associated with science fiction, it can also encompass fantasy, alternate history, and magic realism and be found in music. The term was coined and explored in the late 1990s through exchanges led by Alondra Nelson. Seminal Afrofuturistic works include the novels of Samuel R. Delany and Octavia Butler; the canvases of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Angelbert Metoyer, and the photography of Renée Cox; the cosmic avant-garde jazz of Sun Ra and his Arkestra.

One of his earliest examples of this aesthetic is in his film Space Is the Place, followed by the explicit Parliament-Funkadelic, Earth, Wind, and Fire with their Afrocentric symbolism, performance attire, and promising visions of Black sovereignty. The Jonzun Crew, Warp 9, Deltron 3030, Kool Keith, and the Marvel Comics superhero Black Panther can also be mentioned. Ytasha L. Womack, writer of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, defines it as "an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation." She also follows up with a quote by the curator Ingrid LaFleur, who defines it as "a way of imagining possible futures through a black cultural lens."

Kathy Brown paraphrases Bennett Capers' 2019 work in stating that Afrofuturism is about "forward thinking as well as backward thinking, while having a distressing past, a distressing present, but still looking forward to thriving in the future." Others have said the genre is "fluid and malleable," bringing together technology, African culture, and "other influences." Afrofuturism within music represents a diaspora of non-traditional music focusing on Blackness, space, and technology. It significantly features the sounds of synthesizers and drum machines while incorporating lyrical themes of Black History and cultural pride, progress, spirituality, and science fiction. Studies on Afrofuturistic music highlight the genre's challenging of sonic norms by blending elements found in Hip-Hop, Jazz, R&B, Funk, and electronic music.

Melting together different sounds and cultures with Afrofuturist music emphasizes the otherworldly, alternative nature that defines most Afrofuturist works. When performed live, the genre combines distinct sounds and sound cultures across the African Diaspora. Jamaican American party host DJ Kool Herc was a well-renowned DJ in the 1970s. He was one of the many disc jockeys on the 1970s New York music scene responsible for mixing Jamaica's signature hefty, booming sound systems with R&B and Rap, bass-heavy African American genres. This combination maximized audience immersion and storytelling capabilities.

Afrofuturism as a label fits with George Clinton and his bands Parliament and Funkadelic. Clinton's work and appearance embody Afrofuturistic themes, sporting shiny, futuristic clothing both on and off stage, using sci-fi and cosmic album theming, and addressing Black history in his lyrics. Parliament Funkadelic's strong worldbuilding and establishment of individualism and escapism partly attributed to their inclusion of characters and alter egos in their music. Alter egos remain a staple in Afrofuturistic music, with Janelle Monáe, a notable contemporary musical artist, incorporating characters and sci-fi storylines into their Afrofuturistic music and album visuals. This genre also applies to Jimi Hendrix's songs, such as Electric Ladyland and "Third Stone from the Sun."

Herbie Hancock developed an appreciation for electric and synthesized sounds. He did this throughout the 1970s and 1980s, adopting tribal names for his group in a techno-primitive direction. His record covers were an essential element in this aesthetic, involving artists such as Robert Springett, Victor Moscoso, and Nobuyuki Nakanishi. In 1975, Japanese artist Tadanori Yokoo used aspects of science fiction and Eastern subterranean myths to depict an advanced civilization in his cover art design for Black jazz musician Miles Davis's album Agharta.

Other musicians typically regarded as working in or greatly influenced by the Afrofuturist tradition include reggae producers Lee "Scratch" Perry and Scientist, hip-hop artists Afrika Bambaataa and Tricky, electronic musicians Larry Heard, A Guy Called Gerald, Juan Atkins, Jeff Mills, Newcleus, and Lotti Golden & Richard Scher, writers of "Light Years Away," described as a "cornerstone of early 80's beatbox Afrofuturism." During the 1980s, the growing Detroit techno scene also developed a futurist vision specific to Detroit's suburban Black community. Present-day Afrofuturistic musicians, such as Hip-Hop duo Outkast and composer Nicole Mitchell, have traces of DJ Kool Herc's multicultural influences in their song arrangements and performances, utilizing his signature beat isolation and sound systems decades later.

A newer generation of artists, such as Solange and Erykah Badu, are creating mainstream Afrofuturist music.