*Black History and Britain is affirmed on November 6, 1000.

Historic origins.

Black British people are a multi-ethnic group of British people from Sub-Saharan Africa or the African diaspora. According to the Augustan History, North African Roman emperor Septimus Severus supposedly visited Hadrian's Wall in 210 AD. The body of a girl buried near Eastry in Kent, UK, in the early 7th century had 33% of her DNA of West African type, most closely resembling Esan or Yoruba groups. In 2013, a skeleton in Fairford, Gloucestershire, which forensic anthropology revealed to be that of a Sub-Saharan African woman. Her remains were between the years 896 and 1025. Local historians believe she was likely a slave.

Differences in religion and culture led to Moorish conflicts with Britain. This intersectionality sometimes resulted in marriage. In 1328, Phillippa of Hainault married King Edward III, England's first Black Queen. In 1511, a Black musician was among the six trumpeters depicted in the royal retinue of Henry VIII in the Westminster Tournament Roll. The man was the "John Blanke, the blacke trumpeter," listed in the payment accounts of Henry VIII and his father, Henry VII. A group of Africans at James IV of Scotland's court included Ellen More. Both he and John Blanke were paid wages for their services. Many Black Africans were independent business owners in London in the late 1500s, including the silk weaver.

The Age of Discovery

The Middle Passage opened other commerce lines between London and West Africa, and persons from this area began coming to Britain on board merchant and slaving ships. Merchant John Lok brought several captives from Guinea to London in 1555. During the war with Spain, between 1588 and 1604, there was an increase in the number of people reaching England from Spanish colonial expeditions in parts of Africa. The English freed many of these captives from enslavement on Spanish ships. They arrived in England largely as a by-product of the slave trade; some were of Creole African and Spanish and became interpreters or sailors.

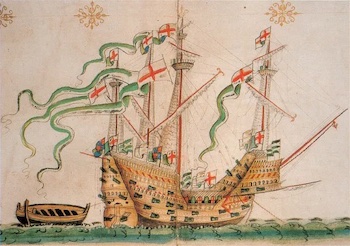

The slave trade became entrenched in the 16th century. Jacques Francis, a slave born on an island off the coast of Guinea, worked as a diver for Pietro Paulo Corsi. This was in salvage operations on the sunken St Mary and St Edward of Southampton and other ships, such as the Mary Rose, which had sunk in Portsmouth Harbor. In March 2019, two of the skeletons found on the Mary Rose had Southern European or North African ancestry; one was found to be wearing a leather wrist-guard bearing the arms of Catherine of Aragon, and royal arms of England were Spanish or North African, possibly, the other, known as "Henry" was also thought to have similar genetic makeup. They likely traveled through Spain or Portugal before arriving in Britain.

A reconstruction of the Mary Rose warship based on an assimilation of geographical, artistic, and historical records

Blackamoor servants were African and perceived as a fashionable novelty and worked in the households of Queen Elizabeth I and several prominent Elizabethans. Some were free workers, domestic servants, and entertainers. Some worked in ports as chattel labor. The African population in England was several hundred during the Elizabethan period (1558-1603); both men and women married native English people.

Archival evidence shows records of more than 360 African people between 1500 and 1640 in England and Scotland. Reacting to the darker complexion of people with biracial parentage, George Best argued in 1578 that Black skin was not related to the heat of the sun (in Africa) but by biblical damnation. In 1601, a Queen Elizabeth I proclamation asserted that the blackamoors were "fostered and powered here, to the great annoyance of [the queen's] own liege people, that covet the relief, which those people consume." It further stated that "most of them are infidels, having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel."

In 1660, the Royal African Company monitored the British interest in the Transatlantic slave trade. Later, they were morphed into the African Company of Merchants in 1752. Britain's involvement in the slave trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas and colonial activities meant ship captains, colonial officials, merchants, slave traders, and plantation owners brought Black slaves as servants back to Britain. This caused an increasing Black presence in London's northern, eastern, and southern areas. This was the most critical factor in developing the current Black British community.

These communities flourished in port cities involved in the slave trade, such as Liverpool and Bristol. As a result, Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest Black community, dating at least to the 1730s. By 1795, Liverpool had 62.5 percent of the European Slave Trade. During this time, Princess Sophie Charlotte, of Moorish ancestry, married George III of England in 1761, becoming Britain's second Black Queen. Officially, slavery was not legal in England. However, Black African slaves continued to be bought and sold in England during the eighteenth century.

The slavery issue was uncontested until the Somerset case of 1772, which concerned James Somerset, a fugitive Black slave from Virginia. Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, concluded that Somerset could not leave England against his will. Legality was often ignored, with slaveowners arguing that the slaves were property and, therefore, could not be considered people.

18th-century Episodes

In 1731 the Lord Mayor of London ruled that "no Negroes shall be bound apprentices to any Tradesman or Artificer of this City." Due to this ruling, most were forced into working as domestic servants and other menial professions and were, in effect, slaves in anything but name. In 1787, Thomas Clarkson, an English abolitionist, noted evidence that Black men and women were discriminated against when dealing with the law because of their skin color. Ignatius Sancho, a Black writer, composer, shopkeeper, and voter in Westminster, became the first Black African to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain at a time when only 3% of the British population was allowed to vote.

Sailors of African descent experienced far less prejudice compared to Blacks in the cities such as London. Black sailors would have shared the same quarters, duties, and pay as their white shipmates. There are some disputes in the estimation of Black sailors; conservative estimates put it between 6% and 8% of navy sailors of the time. Notable examples are Olaudah Equiano and Francis Barber.

Black and mixed-race people in British colonies (Creoles) were also migrants from England and Canada and identified as British. They are generally the descendants of Black people who lived in England in the 18th century and freed Black American slaves who fought for the Crown in the American Revolutionary War (Black Loyalists).

'The loss of America in the 18th century, following the American War of Independence, had been an immense blow to Britain's confidence,' says Sarah Richardson, professor of history at the University of Warwick. In 1787, hundreds of London's Black poor (a category that included the East Indian seamen known as lascars) agreed to go to British Caribbean colonies on the condition that they would retain the status of British subjects, live in freedom under the protection of the British Crown, and defended by the Royal Navy. Making this fresh start with them were some white people, including lovers, wives, and widows of the Black men. In addition, nearly 1200 Black Loyalists, former American slaves who had been freed and resettled in Nova Scotia, and 550 Jamaican Maroons also chose to join the new colony.

Rise in the Black population.

Black people lived among whites in London's Mile End, Stepney, Paddington, and St Giles and continued to work for their old masters as paid employees. Between 14,000 and 15,000 (then contemporary estimates) slaves were immediately freed in England after Mansfield's rule. Many of these emancipated individuals became labeled as the "black poor," defined as former slave soldiers since emancipated seafarers, such as South Asian lascars, former indentured servants, and former indentured plantation workers. Around the 1750s, London became the home to many Blacks, Jews, Irish, Germans and Huguenots.

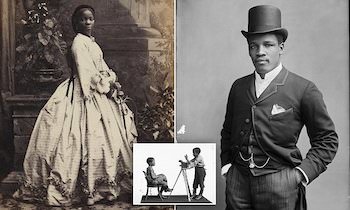

According to Gretchen Gerzina in her Black London, by the mid-18th century, Blacks accounted for between 1% and 3% of the London populace. Registered burials show evidence of the number of Black residents in the city. Some black people in London resisted slavery through escape. Leading Black abolitionists of this era included Equiano, Ignatius Sancho, and Ottobah Cugoano. Mixed-race Dido Elizabeth Belle, who was born into slavery in the Caribbean, moved to Britain with her white father in the 1760s. In 1764, there were nearly 20,000 African servants.

John Ystumllyn, a West African slave, was the first recorded Black person in North Wales. He was taken in by the Wynn family to their Ystumllyn estate and christened with his Welsh name. He became a gardener at the estate and married local woman Margaret Gruffydd in 1768. their descendants still live in the area. Based on parish lists, baptismal and marriage registers, and criminal and sales contracts, modern historians estimate that about 10,000 Black people lived in Britain during the 18th century. In 1772, Lord Mansfield put the number of Black people in the country at as many as 15,000, though most modern historians consider 10,000 to be the most likely. The Black population was estimated at around 10,000 in London, making Black people approximately 1% of the overall London population.

The Black population constituted around 0.1% of the total population of Britain in 1780. The Black female population is estimated to have barely reached 20% of the overall Afro-Caribbean population in the country. In the 1780s, after the American Revolutionary War, hundreds of Black loyalists from America were resettled in Britain. Later, some emigrated to Sierra Leone, with help from the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor after suffering destitution, to form the Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.

When Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, the British Empire was a loose assortment of colonies mostly accrued for trade reasons. By her death, nearly 64 years later, the Empire had expanded to become a coherent and dominant show of economic and political strength. Queen Victoria presided over almost a quarter of the world's population as head of state. At the turn of the 20th century, the Union flag was raised from the farthest reaches of North America, across the Caribbean, over large swathes of Africa, throughout the Indian subcontinent, and as far distant as Australia and New Zealand. The cliché about Britain's influence, power, and control was that the 'Sun never set on its empire.'

Abolitionism

With the support of other Britons, these activists demanded that Blacks be freed from slavery. Supporters involved in these movements included workers and people of other nationalities, including the urban poor. Black people in London who were supporters of the abolitionist movement include Cugoano and Equiano. Slavery in Britain was not clearly defined until the 19th century. According to the 1909 book Britons Through Negro Spectacles, London's Black population at the time was one Black person in London to over sixty thousand whites.

World War I saw a slight growth in the size of London's Black communities with the arrival of merchant seamen and soldiers. At that time, small groups of students from Africa and the Caribbean were migrating to London. These communities are now among the oldest Black communities in London. London's East End, Liverpool, Bristol, and Cardiff's Tiger Bay were the most significant Black communities. In 1914, the Black population was estimated at 10,000 and centered mainly in London. By 1918, there may have been as many as 30,000 Black people living in Britain who emigrated from parts of the British Empire.

The number of Black soldiers serving in the British army (rather than colonial regiments) before World War I is unknown but was likely to have been negligibly low. One of the Black British soldiers during World War I was Walter Tull, an English professional footballer, who became the first British-born mixed-heritage infantry officer in a regular British Army regiment, despite the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluding soldiers that were not "of pure European descent" from becoming commissioned officers.

Colonial Afro Caribbean soldiers and sailors served in the United Kingdom during the First World War, and some settled in Britain. The South Shields community included other 'Coloured' seamen from South Asia and the Arab world who died in the UK's first race riot in 1919. Soon, eight other cities with significant nonwhite communities had race riots. Due to these disturbances, many of the residents from the Arab world, as well as some other immigrants, were evacuated to their homelands. In that first postwar summer, other racial riots of whites against nonwhites took place in United States cities, the Caribbean, and South Africa. They were part of the social dislocation after the war as societies struggled to integrate veterans into the workforce again, as well as the job and housing competition.

At Australian insistence, the British refused to accept the Racial Equality Proposal put forward by the Japanese at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. World War II marked another period of growth for the Black communities in London, Liverpool, and elsewhere in Britain. Many Blacks from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived in small groups as wartime workers, merchant seamen, and men from the army, navy, and air forces. For example, in February 1941, 345 West Indians came to work in factories in and around Liverpool, making munitions. Among those from the Caribbean who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) and gave distinguished service are Ulric Cross from Trinidad, Cy Grant from Guyana, and Billy Strachan from Jamaica.

By the end of 1943, 3,312 African American GIs were from Maghull and Huyton, near Liverpool. In the summer of 1944, the Black population was estimated at 150,000, mostly Black GIs from the United States. However, by 1948, the Black population was estimated to have been less than 20,000. The African and Caribbean War Memorial was installed in Brixton, London, in 2017 by the Nubian Jak Community Trust to honor men from Africa and the Caribbean who served alongside British and Commonwealth Forces in the First and Second World Wars.

Discrimination

Learie Constantine, a West Indian cricketer, was a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labor when he was refused service at a London hotel in 1943. He sued for breach of contract and got damages. This illustrates the slow change from racism towards acceptance and equality of all citizens in London. In 1943, Amelia King was refused work by the Essex branch of the Women's Land Army because she was Black. The decision was overturned. The term Black British emerged in the 1950s, referring to the Black British West Indian people from the former Caribbean British colonies in the West Indies (i.e., the New Commonwealth), sometimes referred to as the Windrush Generation, and Black British people descending from Africa.

Over a quarter of a million West Indians, mainly from Jamaica, were settled in Britain in less than a decade. In 1951, Britain's population of Caribbean and African-born people was 20,900. Black British did not become widespread use until the second generation was born to these post-war migrants in the UK. Although British by nationality, due to friction between them and the White majority, they were often born into relatively closed communities, creating the roots of what would become a distinct Black British identity. By the 1950s, there was a consciousness of Black people as a separate group that had not been there during 1932–1938. The influx deeply informed the increasing consciousness of the Black British community of Black American culture imported by Black servicemen during and after World War II.

These close interactions between African Americans and Black British were not only material but also inspired the expatriation of some Black British women to America after marrying service members (some of whom later repatriated to the UK). In 1961, the population of people born in Africa or the Caribbean was estimated at 191,600, just under 0.4% of the total UK population. The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in Britain, which severely restricted the entry of Blacks into Britain. During this period, Blacks and Asians struggled in Britain against racism and prejudice. During the 1970s—and partly from racial intolerance and the rise of the Black Power movement abroad Black had a negative meaning and was recovered as pride: black is beautiful.

In 1975, David Pitt was appointed to the House of Lords. He spoke against racism and for equality for all residents of Britain. In the years that followed, several Black members came into the British Parliament. By 1981, the Black population in the United Kingdom was estimated at 1.2% of all countries of birth, being 0.8% Black-Caribbean, 0.3% Black-Other, and 0.1% Black-African residents. Since the 1980s, the majority of Black immigrants into the country have come directly from Africa, particularly Nigeria and Ghana, Uganda, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, all former colonies.

Young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieve the best academic results, often on par with or above the performance of white pupils. Black British is one of various self-identities used in official UK ethnicity classifications. Due to the Indian diaspora, and notably Idi Amin's expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972, many British Asians are from families that had previously lived for several generations in the British West Indies or the Comoros. Several British Asians use the terms "Black" and "Asian" interchangeably.

Language

Black British refers to Black people of New Commonwealth origin and West African and South Asian descent. Black was used in this inclusive political sense to mean 'nonwhite British.' In the 1970s, in the fight against racism, the central communities described were from the British West Indies and the Indian subcontinent and sometimes included the Irish population of Britain. Several organizations continue to use the term inclusively, such as the Black Arts Alliance and the National Black Police Association. The official UK Census has separate self-designation entries for 'Asian British,' 'Black British,' and 'Other ethnic group.'

Census classification

The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity. As of the 2011 UK Census, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) allow people in England and Wales and Northern Ireland who self-identify as 'Black' to select 'Black African,'' Black Caribbean' or any other 'Black/African/Caribbean background' tick boxes. For the 2011 Scottish census, the General Register Office for Scotland (GOS) also established new, separate 'African, African Scottish or African British' and 'Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British' tick boxes for individuals in Scotland from Africa and the Caribbean, respectively, who do not identify as 'Black, Black Scottish or Black British.' Around 3.7 percent of the United Kingdom's population in 2021 were Black. The figures had increased from the 1991 census when 1.63 percent of the population was recorded as Black or Black British to 1.15 million residents in 2001 or 2 percent of the population; this further increased to just over 1.9 million in 2011, representing 3 percent. Almost 96 percent of Black Britons live in England, particularly in England's larger urban areas, with close to 1.2 million living in Greater London.

The 2021 census in England and Wales maintained the Caribbean, African, and any other Black, Black British, or Caribbean background options, adding a write-in response for the 'Black African' group. In Northern Ireland, the 2021 census had Black African and Black Other tick-boxes. In Scotland, the options were African, Scottish, African, British, African, and Caribbean or Black, each accompanied by a write-in response box. In all the UK censuses, persons with multiple familial ancestries can write in their respective ethnicities under a "Mixed or multiple ethnic groups" option, which includes additional "White and Black Caribbean" or "White and Black African" tick boxes in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity. As of the 2011 UK Census, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) allow people in England and Wales and Northern Ireland who self-identify as 'Black' to select 'Black African,'' Black Caribbean' or any other 'Black/African/Caribbean background' tick boxes. For the 2011 Scottish census, the General Register Office for Scotland (GOS) also established new, separate 'African, African Scottish or African British' and 'Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British' tick boxes for individuals in Scotland from Africa and the Caribbean, respectively, who do not identify as 'Black, Black Scottish or Black British.' Around 3.7 percent of the United Kingdom's population in 2021 were Black.

The figures had increased from the 1991 census when 1.63 percent of the population was recorded as Black or Black British to 1.15 million residents in 2001 or 2 percent of the population; this further increased to just over 1.9 million in 2011, representing 3 percent. Almost 96 percent of Black Britons live in England, particularly in England's larger urban areas, with close to 1.2 million living in Greater London. The 2021 census in England and Wales maintained the Caribbean, African, and any other Black, Black British, or Caribbean background options, adding a write-in response for the 'Black African' group.

In Northern Ireland, the 2021 census had Black African and Black Other tick-boxes. In Scotland, the options were African, Scottish, African, British, African, and Caribbean or Black, each accompanied by a write-in response box. In all the UK censuses, persons with multiple familial ancestries can write in their respective ethnicities under a "Mixed or multiple ethnic groups" option, which includes additional "White and Black Caribbean" or "White and Black African" tick boxes in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Imtiaz Habib's Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Ashgate, 2008),

Onyeka's Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins (Narrative Eye, 2013),

Miranda Kaufmann's Oxford DPhil thesis Africans in Britain, 1500–1640, and her Black Tudors: The Untold Story (Oneworld Publications, 2017).

Black and British, A Forgotten Story by David Olusoga, Picador Publishing, 2021, ISBN 978-15290-6560-2