'Mammy'

*Black history and the term 'Mammy' is affirmed on March 24, 1830. This is a historical American labeled stereotype describing Black women, usually enslaved, doing domestic work, including nursing white children of slave owners.

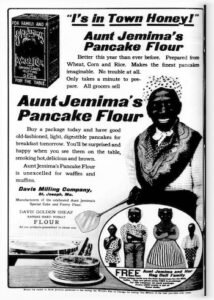

The fictionalized mammy character is often a dark-skinned woman with a motherly personality. The origin of the mammy figure stereotype is rooted in the history of slavery in the United States, as enslaved women were domestic and childcare workers in American slave-holding households. The mammy caricature was first seen in the 1830s in Antebellum pro-slavery literature as a form to oppose the description of slavery given by abolitionists. One of the earliest fictionalized versions of the mammy figure is Aunt Chloe in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, first published in 1852.

The mammy caricature created a narrative of Black women being content within the institution of slavery and domestic servitude. The mammy stereotype associates Black women with domestic roles, and it is debated that segregation and discrimination limited job opportunities for Black women during the Jim Crow era (1877 to 1966). In 1923, the United Daughters of the Confederacy proposed erecting a mammy statue on the National Mall. The proposed statue would have been dedicated to "The Black Mammy of the South." The bill received a standing ovation in the Senate, where it passed with bipartisan consensus, but died in committee in the House following written protests from thousands of Black women.

Scholars see the mammy figure's duties included preparing meals, cleaning homes, and nursing and rearing their owners' children. While originating in the slavery period, the mammy figure rose to prominence during the Reconstruction Era. Scholars may argue that the Southern United States has a mammy role in reinterpreting and legitimizing the legacy of chattel slavery and racial oppression. Televisions did not become common in U.S. households until around the mid to late 1940s, making radio shows popular entertainment for the American family. In 1939, Beulah Brown debuted as a character on the radio show Homeward Unincorporated. Beulah, as a character, was highly stereotypical and was the quintessential mammy figure auditorily.

White actor Marlin Hurt originally played the character. The character was added to several other radio shows. Over time, the creators and producers of these shows wanted to have an actual Black woman as the character's voice. Hattie McDaniel had the role on the radio version in 1947, as she was famous for her multiple other award-winning performances portraying the mammy stereotype. The radio show was taken to television in the early 1950s and went on to run for three seasons. The show's first season starred Ethel Waters, who later left the series for no longer wanting to portray the mammy stereotype. McDaniel took over the role for the second season, filming six episodes before becoming ill. McDaniel played these mammy roles repeatedly, as they were the only accessible roles for Black actresses during this time. McDaniel was the epitome of what a mammy looked like and was big, with a large mouth and dark skin that contrasted with white teeth and big eyes, needless values of white perceptions. Louise Beavers also portrayed the role on television.

Aside from the actress that portrayed her, Beulah, as a character, had all the characteristics of a mammy. She always ensured her "family," the family she worked for, was well cared for. Helping them at any cost and putting their needs above her own can be seen in multiple show episodes. The NAACP and other critics did not like the image of Black women the show represented as the mammy stereotype. In the early 20th century, the mammy character was common in many films. Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress with her performance as "Mammy" in Gone with the Wind in 1939. In 1940, shortly after the win, the NAACP scrutinized McDaniel's role and criticized Hollywood for lacking diverse Black roles and characters outside of servitude. McDaniel responded to the backlash by saying, "Why should I complain about making $7,000 playing a maid? If I didn't, I'd be making $7 a week being one."

The mammy image continues to be reproduced into the 21st century. Some contemporary media portrayals of the mammy caricature have been seen in Big Momma's House, starring Martin Lawrence. In the movie, the character of Big Momma is a plus-size, older Black matriarch and homemaker with overtly religious beliefs and a nurturing demeanor. Another mammy stereotype that the movie displays is the one of midwifery and domestic work. Again, this originates from the history of older Black women serving as midwives on plantations. Also, in the 21st century, stereotypical or controlling images of Black women reflect the economic, legal, and social changes that have occurred in Blacks over the past 50–60 years.

The images also reflect a society as a whole: a global economy, unprecedented media reach, and transitional racial inequality, and are more class-specific. Working-class Black women are sometimes depicted as the "Bad Black Mother"/" Welfare Queen" and the "Bitch” (materialistic and hyper-sexual Black women within "hip-hop" "Rap" culture), Middle-class Black women are depicted as "Black Ladies" with allegedly un-restrained sexual desire. An educated Black woman is often depicted as an "Educated Black Bitch” who is portrayed as manipulative and controlling.

These Black women in positions of power are often seen as the "Modern-day Mammy," which now refers to a well-educated and successful Black woman within the upper/upper middle class who "uphold[s] white-dominated structures, institutions, or bosses at the expense of [her] personal [life]." This can be an imitation of the original "Mammy" stereotype, in which the Black woman was not only subservient but often happy to serve her white enslaver.