Oliver le Jeune

*The Canadian Slavery of Africans is affirmed on this date, circa 1600. We begin with the registered baptism of Olivier Le Jeune, which occurred on this date in 1633 in Quebec.

The Middle Passage and its British involvement preceded this Canadian baptism. This was the first official registration of Canadian slavery; Le Jeune was the first recorded slave purchased in Canada (New France). This Negro boy belonged to Guillaume Couillard, a French Seaman and Carpenter. Olivier was from Madagascar and believed to have been less than eight years of age in 1629 when British commander David Kirke brought him to Quebec in New France. Shortly after his arrival, the boy was sold to Olivier Le Baillif, a French clerk for Britain. Olivier le Jeune's name is consistent with Canada’s Code Noir, which was not officially established until 1685. The Code Noir forced baptisms and decreed the conversion of all slaves to Catholicism.

By 1688, New France's population was 11,562 people, made up primarily of fur traders, missionaries, and farmers settled along the St. Lawrence Valley. To help overcome its severe shortage of servants and laborers, King Louis XIV granted New France permission to import Black slaves from West Africa. While slavery was prohibited in France, it was permitted in its colonies to provide the labor force needed to clear land, construct buildings, and (in the Caribbean colonies) work sugar plantations. ‘Code Noir' defined the control, management, and pattern for policing slavery. It required that all slaves be instructed as Catholics and not as Protestants. It concentrated on defining the condition of slavery and established harsh controls. Slaves had virtually no rights, though the Code did enjoin masters to take care of the sick and old. Blacks were usually called "servants," and the death rates among slaves were high.

Marie Joseph Angélique was the black slave of a wealthy widow in Montreal. According to a published account of her life in 1734, after learning that she would be sold and separated from her community, she set fire to her owner's house and escaped. The fire destroyed forty-six buildings. Captured two months later, Marie-Joseph was paraded through the city and tortured until she confessed her crime. In the afternoon of the day of execution, she was taken one last time through the streets of Montreal and, after the stop at the church to make amends facing the ruins of the buildings destroyed by the fire, she was hanged, her body flung into the fire and the ashes scattered in the wind. In 1759, before the British conquest, Historian Marcel Trudel recorded approximately 4000 slaves; 2,472 were aboriginal people, and 1,132 were black. After the British Conquest, slave ownership remained dominated by the French. Trudel identified 1509 slave owners, of whom only 181 were English, and 31 marriages occurred between French colonists and Aboriginal slaves.

Canadian First Nations owned or traded slaves, an institution that had existed for centuries or longer among certain groups. Shawnee, Potawatomi, and other western tribes imported slaves from Ohio and Kentucky and sold them to Canadian settlers. Black slaves who lived in the British regions of Canada in the 17th and 18th centuries numbered 104, as listed in a 1767 census of Nova Scotia. Still, their numbers were small until the United Empire Loyalist influx after 1783.

As white Loyalists fled the new American Republic, they took with them about 2000 black slaves: 1200 to the Maritime Provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island), 300 to Lower Canada (Quebec), and 500 to Upper Canada (Ontario). In Ontario, the Imperial Act of 1790 assured prospective immigrants that their slaves would remain their property. Under French rule, Loyalist slaves were held in small numbers and were employed as domestic servants, farmhands, and skilled artisans. Slavery in Canada was neither banned nor permitted in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the Quebec Act of 1774, or the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The gang labor system and its institutions of control and brutality did not develop in Canada as they did in the United States of America. Because they did not appear to threaten their masters, slaves were permitted to learn to read and write, Christian conversion was encouraged, and the law recognized their marriages.

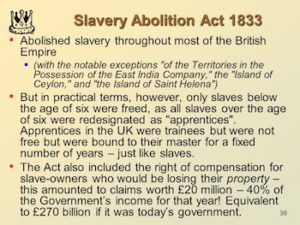

The July 12, 1787, Quebec Gazette had a classified ad: For sale, a robust Negress, active and with good hearing, about 18 years old, who has had small-pox, has been accustomed to household duties, understands the kitchen, knows how to wash, iron, sew, and very used to caring for children. She can adapt equally to an English, French, or German family; she speaks all three languages. While many free Blacks arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, others did not. Black slaves also arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of White American Loyalists. In 1772, before the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles, followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the emancipated colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian Church who owned slaves. In 1790, John Burbidge freed his slaves. Led by Richard John Uniacke, in 1787, 1789, and again on January 11, 1808, the Nova Scotia legislature refused to legalize slavery. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumsden Strange and Sampson Salter Blowers, were instrumental in freeing slaves from their owners in Nova Scotia. They were held in high regard in the colony. By the end of the War of 1812 and the arrival of the Black Refugees, there were few slaves left in Nova Scotia. (The Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807, and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 prohibited slavery altogether.)

The Sierra Leone Company was established to relocate groups of formerly enslaved Africans, nearly 1,200 from the black Nova Scotia community, most of whom had escaped enslavement in the United States. Given the coastal environment of Nova Scotia, many had died from the harsh winters there. They established a settlement in the existing colony in Sierra Leone (already established to house the 'poor Blacks' of London) at Freetown in 1792. Many of the "Black poor" were African Americans who had been promised their freedom for joining the British Army during the American Revolution, but also included other African and Asian inhabitants of London. The Freetown settlement was joined, particularly after 1834, by other groups of freed Africans and became the first African haven for formerly enslaved Africans in North America. Near the end of the 18th century, the abolition movement was gaining acceptance in Canada. The ill intent of slavery was evidenced by an incident involving a slave woman being violently abused by her slave owner on her way to being sold in the United States.

In 1793, Chloe Clooey yelled out screams of resistance in defiance. Peter Martin and William Grisely witnessed the abuse committed by her slave owner and her violent resistance. Martin, a former slave, brought the incident to the attention of Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe. Under the auspices of Simcoe, The Act Against Slavery of 1793 legislated the gradual abolition of slavery: no slaves could be imported; slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death; no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at age 25. To discourage manumission, the Act required the master to provide security that the former slave would not become a public charge.

The Compromise Act Against Slavery is the only attempt by any Ontario legislature to act against slavery. This legal rule ensured the eventual end of slavery in Upper Canada. However, as it diminished the sale value of slaves within the province, it also resulted in slaves being sold to the United States. In 1798, lobby groups attempted to rectify the legislation and import more slaves. By 1800, the other provinces of British North America had effectively limited slavery through court decisions requiring the strictest proof of ownership, which was rarely available. In 1819, the Attorney General of Upper Canada, John Robinson, declared that Black residents were set free by residing in Canada and that Canadian courts would protect their freedom.

In Nova Scotia, former slave Richard Preston established the African Abolition Society in the fight to end slavery in America. Preston was trained as a minister in England. He met many leading voices in the abolitionist movement that helped inform the conversation and language of the Slavery Abolition Act. When Preston returned to Nova Scotia, he became the president of the Abolitionist movement in Halifax. Preston stated: The time will come when slavery will be just one of our many travails. Our children and their children’s children will mature to become indifferent toward climate and indifferent toward race. Then we will desire. Nay, we will demand, and we will be able to obtain our fair share of wealth, status, and prestige, including political power. Our time will have come, and we will be ready; we must be. However, slavery remained legal until the British Parliament's Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 finally abolished it in all parts of the British Empire. This went into effect on August 1, 1834.

Approaching the time of American Emancipation, before the American Civil War, the Underground Railroad network had been established in the United States, particularly Ohio, where slaves would cross into the Northern States over the Ohio River en route to various settlements and towns in Upper Canada (known as Canada West from 1841 to 1867, now Ontario). This is Canada's only relationship to slavery, generally known to the public or acknowledged by the Canadian government.

In the 20th century, Canadian slavery did not end with the ratification of the Slavery Convention in 1953. Human trafficking in Canada remains a significant legal and political issue, and Canadian legislators have been criticized for having failed to deal with the problem more systematically. British Columbia's Office to Combat Trafficking in Persons was formed in 2007, the first province of Canada to address human trafficking formally. The most significant human trafficking case in Canadian history involved dismantling the Domotor-Kolompar criminal organization. In 2012, Canada established a National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking. The Human Trafficking Taskforce was established in that same year to replace the Interdepartmental Working Group on Trafficking in Persons as the body responsible for the development of public policy related to human trafficking in Canada.

One publicized instance is the vast "disappearances" of Aboriginal women, which have been linked to human trafficking by some sources. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper had been reluctant to tackle the issue because it is not a "sociological issue" and declined to create a national inquiry into the matter counter to what his opponents say are United Nations and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights' opinions that the issue is significant and in need of higher inquiry.

Oliver le Jeune’s recorded life began with his christening and affirms this article on Canada’s involvement in African slavery. Because early Canada's role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade was so minor, the history of slavery in Canada is often overshadowed by the more tumultuous slavery practiced elsewhere in the Americas, especially in the American South and the colonial Caribbean. Olivier Le Jeune died on May 10, 1654. It is believed that by his death, his official status was changed from slave to free "domestic servant." Today, there are four remaining slave cemeteries in Canada: St-Armand, Quebec, Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and Priceville and Dresden in Ontario.

Afua Cooper, Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology

McCain Building, 6135 University Avenue

PO Box 15000, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 4R2

Marcel Trudel, Canadian Historian