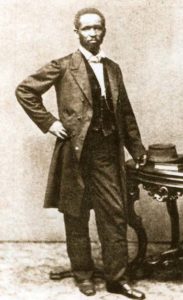

Lewis Hayden

*Lewis Hayden was born on this date in 1811. He was a Black politician and abolitionist.

From Lexington, KY. He was one of 25 children. His mother was of mixed race, African, European and Native American. Hayden was first owned by a Presbyterian minister, Rev. Adam Rankin who sold off his brothers and sisters in preparation for moving to Pennsylvania; he traded 10-year-old Hayden for two carriage horses to a man who traveled the state selling clocks. The travels with his new master allowed Hayden to hear varying opinions of slavery, including its classification as a crime by some people.

In 1830, he married Esther Harvey, also a slave. After his first wife, Esther, was sold away from him, Hayden remarried fellow slave, Harriet, and adopted her son, William. After being let out by his master as a waiter in the Phoenix Hotel in Lexington, Hayden began to teach himself how to read and write from the pieces of discarded newspaper he collected off the streets. An abolitionist from Vermont, Delia Webster, met Hayden one day while dining at the Phoenix Hotel. Impressed by his literacy and intelligence, she introduced him to Calvin Fairbank, an abolitionist ministerial student from Oberlin, OH.

In 1844, Calvin Fairbank arrived in Lexington to assist in the rescue of a slave but, when the plans for that rescue fell through, he agreed to transport Lewis, his wife Harriet, and their son, William, across the Ohio River to freedom. During the journey, traveling through the darkness of night, Calvin Fairbank asked Hayden why he wanted to be free, and Hayden responded, "because I am a man." By 1845, Hayden had moved to Detroit, MI, where he assisted Black minister John M. Brown in founding the city's Bethel AME church.

During a visit to Boston to raise money for the church, Hayden and Brown met and joined forces with members of Boston's abolitionist community, including Theodore Parker, Wendell Phillips, Maria Weston Chapman, John Andrew and William Lloyd Garrison. Impressed by Hayden's natural leadership ability and commitment to social justice, Garrison appointed him traveling speaker with the American Anti-Slavery Society. Before returning to Detroit, Hayden spoke to and allied himself with various New England social reformers and intellectuals, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Hayden was so inspired by the commitment of the Massachusetts abolitionist community to freedom that he moved Harriet and William to New Bedford, and by 1848, had moved to a home on Phillips street in Boston's Beacon Hill.

This house, at 66 Phillips Street, became a boarding house and a frequent meeting place for activists on the Underground Railroad, while his used clothing business, located on Cambridge Street with a stock valued at over $10,000, became the second-largest Black owned business in the city. With professional success, social status, and financial stability, Hayden continued to act as a leader in the struggle for Black freedom and equality, both nationally and locally. One of his first priorities was to raise money for the release of Calvin Fairbank, sent to prison in 1845 for assisting the Hayden’s in their escape from Kentucky. Hayden's former owners had agreed to petition the Kentucky courts to suspend Fairbank's fifteen-year sentence in exchange for $650. Hayden, using his network of influential abolitionist friends (particularly Phillips and Francis Jackson), raised this amount, sent it to Kentucky, and received notice that Fairbank had been released from prison on August 24, 1849.

Through this act, Hayden proved his ability to galvanize citizens, Black and white, poor and wealthy for the cause of freedom. This ability was just what Boston needed after the passage of the hated Fugitive Slave Law in 1850. Two weeks after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, on September 30, 1850, Lewis Hayden organized a meeting at the African Meeting House "for the colored citizens of Boston." With fellow abolitionists John T. Hilton, William C. Nell, and William Lloyd Garrison, Hayden helped channel the community's outrage and fear into militant resistance to the law, stating: "they who would be free themselves must strike the blow." This meeting, and Hayden's strong advocacy for community protest, reverberated far beyond the city's Black community, resulting in the founding of the bi-racial Boston Vigilance Committee on October 14, 1850.

Pledging "to take all measures which [we] shall deem expedient to protect the colored people of this city in the enjoyment of their lives and liberties," this group, with Hayden as the leader of the executive committee, had over 50 middle-class, abolitionist, and professional members. These members included: Phillips, Jackson, John Andrew, Robert Morris, John T. Hilton, and Rev. Theodore Parker. From 1850 until the start of the American Civil War, the Boston Vigilance Committee raised money, provided legal defense, and resisted federal marshals on behalf of fugitive slaves. During the 1850s, there were four fugitive slave cases in Boston. The battles waged between federal marshals, slave catchers, and Boston's abolitionist community as a result of these cases placed Lewis Hayden at the top of his game.

Whether transforming his home into a fortress during the rescue of William and Ellen Craft, galvanizing common folk and Vigilance Committee members in the rescue of Shadrach Minkins, or leading attacks on the courthouses where Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns were kept, Hayden was one of the leading figures in the battle waged between federal marshals, slave catchers, and Boston's abolitionist community. In addition, Hayden remained a leading member of the African Masonic Lodge, becoming National Deputy Grand Master, serving as lodge delegate to the National Convention of Black Masons, and initiating a petition for the legal recognition of Black masonry within the White Masonic order. Between 1857 and 1859, radical white freedom fighter John Brown visited Boston seven times to gain money and manpower for his planned raid on Harper's Ferry, WV. While in Boston, he not only stayed at Hayden's boarding house on Phillips street, but he also solicited Hayden's assistance in fundraising and support.

Just two months before his ill-fated raid on Harper's Ferry, Brown approached Hayden, requesting $500; Hayden managed to raise $600 in gold from Francis Merriam, grandson of Vigilance Committee treasurer Francis Jackson. This was a daring act, considering Hayden had been appointed messenger to the Massachusetts Secretary of State, at that time the highest civil service position held by a Black man in the state's history. He held this position for over thirty years while maintaining support for Black and white activists across the north. During the war, Hayden helped recruit volunteers for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Before the war was over, Hayden's only son, William, died with members of the Fifty-fourth at the Battle of Fort Wagner, July 18, 1863. From emancipation until his death in 1889, Hayden remained active in freedom struggles throughout Boston.

His activism included: representing the predominantly Black Beacon Hill neighborhood (Ward 6) in the state senate; advocating for woman's suffrage; founding the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; becoming a benefactor to the Massachusetts Historical Society; serving as an alternate to the national Republican Convention; and leading a successful petition to erect a monument to Crispus Attucks in 1887. Upon his death from renal disease on April 7, 1889, a funeral was held at the Charles Street AME church that was attended by over 1200 mourners, both Black and white, including former abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Four years later, Hayden made his final contribution to the future of Black freedom when his wife died, releasing the remains of her husband's estate (valued at over $5000) to Harvard University Medical School. The money was used to establish a scholarship fund for qualified Black medical students, at a time when Blacks were not permitted to attend the school and, reportedly, were prevented from walking on school grounds.

Robert, Stanley J. and Anita W.

"Lewis Hayden: From Fugitive Slave to Statesman"

in The New England Quarterly vol. 46, number 4, Dec. 1973.

The Bostonian Society

Lewis Hayden and the War Against Slavery

by Joel Strangis

2000 Books for the Teen Age, New York Public Library

Image: Houghton Library Harvard University