*The Massacre at Ebenezer Creek on this date in 1864. During the American Civil War, hundreds of Black families who had just escaped slavery were left to drown by Union General Jeff. C. Davis.

In November 1864, Union General William T. Sherman heard of atrocities at Camp Lawton, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp near Millen, Georgia. Sherman ordered his troops to begin marching South toward the camp. He found it deserted. He ordered the entire camp burned to the ground and his troops to continue moving south to pursue the Confederates who had vacated the camp. His troops began to attract many enslaved people. There are reports that by the time the soldiers reached Ebenezer Swamp, there were over 2,000 enslaved people.

Throughout Sherman's March to the Sea, enslaved people were considered "a growing burden" as the army approached Savannah in December 1864. Complicating the situation, Confederate cavalry under General Joseph Wheeler harassed the Federal rear guard upon reaching the area surrounding Ebenezer Swamp, General Jeff. C. Davis' troops found that the heavy rains caused the riverbanks to overflow, washing away the roads.

They found a destroyed bridge over Ebenezer Creek, the only way to cross the swamp. Confederates had begun to fire upon the Union soldiers from along the Savannah River. On December 8, 1864, the Union XIV Corps reached the western bank of Ebenezer Creek. While their engineers assembled a pontoon bridge for the crossing, Wheeler's cavalry approached close enough to conduct sporadic shelling of the Union lines. The bridge was ready by midnight, and Davis's 14,000 men began crossing. Over 600 freed people were anxious to cross with them, but Davis ordered his provost marshal to prevent this.

The freedmen were told to cross after a Confederate force in front had been dispersed. No such party existed. As the last Union soldiers reached the eastern bank on December 9, Davis's engineers cut the bridge loose and drew it onto the shore. The refugees cried out as their escape route was pulled away from them. Moments later, Wheeler's scouts rode up from behind and opened fire. On realizing their plight, a panic set in amongst the freedmen, who knew that Confederate cavalry was nearby.

They "hesitated briefly, impacted by a surge of pressure from the rear, then stampeded with a rush into the icy water, old and young alike, men and women and children, swimmers and non-swimmers, determined not to be left behind." In the uncontrolled, terrified crush, many quickly drowned. Some of Davis's soldiers tried to help those they could reach on the eastern bank, wading into the water as far as they dared. Others felled trees into the water.

Several freedmen lashed logs together into a crude raft, which they used to rescue those they could and then ferry others across the stream. Several Union soldiers on the eastern bank tried to help, pushing logs out to the few refugees still swimming. While these efforts were underway, Wheeler's Confederate cavalry scouts arrived, fired at the soldiers on the far bank, and left to summon Wheeler's full force. Officers from the XIV Corps ordered their men to leave.

The freedmen continued to ferry many across the stream on the makeshift raft. Still, when Wheeler's cavalry arrived in force, those refugees who had not made it to the eastern bank or drowned in the attempt were enslaved once more. Davis's orders infuriated several Union men who witnessed the ensuing calamity, Major James A. Connolly and Chaplain John J. Hight. Connolly described the events in a letter to the Senate Military Commission, which entered the press. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton brought the incident up with Sherman and Davis during a visit to Savannah in January 1865.

Davis defended his actions as a military necessity with Sherman's support. From an article in The Washington Post, "On the pretense that there was likely to be fighting in front, the negroes were told not to go upon the pontoon-bridge until all the troops and wagons were over a guard was detailed to enforce the order," recalled Col. Charles Kerr of the 16th Illinois Cavalry in a speech 20 years after the incident. "As soon as we were over the creek, orders were given to the engineers to take up the pontoons and not let a negro cross. I sat upon my horse then and witnessed a scene the like of which I pray my eyes may never see again."

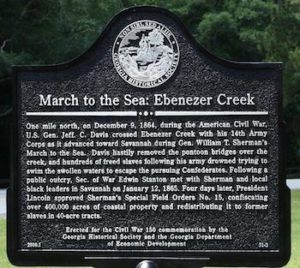

In 2010, the Georgia Historical Society erected a "March to the Sea: Ebenezer Creek" marker near the site to recognize the 1864 tragedy and its outcome.