*The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created on this date in 1941. Officially termed Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, its purpose was: "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and companies engaged in war-related work."

This was a significant advancement for African Americans, initiated primarily by three individuals and organizations. Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters President A. Philip Randolph, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White, and National Youth Administration Minority Affairs Director Mary McLeod Bethune were instrumental in forcing FDR to address the issue.

FEPC was established shortly before the United States entered World War II. The executive order also required federal vocational and training programs to be administered without discrimination. Established in the Office of Production Management, the FEPC was intended to help African Americans and other minorities obtain jobs in home-front industries during World War II. In practice, especially in its later years, the Committee also tried to open more skilled jobs in industry to nonwhites, who had often been restricted to the lowest-level work. The FEPC appeared to have contributed to substantial economic improvements among Black men during the 1940s by helping them enter more skilled and higher-paying positions in defense-related industries.

In January 1942, following the United States' entry into World War II, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9040 to establish the War Production Board, which replaced the Office of Production Management and placed the FEPC under its authority, reporting to the War Manpower Commission. The new Board, concentrating on converting the domestic economy to a wartime footing, slashed the Committee's limited budget. In response to strong support for the FEPC and a threatened march on the capital, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9346 in May 1943. This gave the FEPC independent status within the Office of the President and established 16 regional offices. It widened its jurisdiction to all federal agencies and those directly involved in defense. It was put within the President's Office of Emergency Management.

The order banned racial discrimination in any defense industry receiving federal contracts by declaring, "there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin." The order also empowered the FEPC to investigate complaints and take action against alleged employment discrimination. Working with other civil rights activists, Randolph organized a 1941 March on Washington Movement to protest racial discrimination in the defense industry and the military. This threatened to bring 250,000 African Americans to Washington to demonstrate congressional resistance to fair employment.

FDR sent his wife, Eleanor, and New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to negotiate with the leaders of the March on Washington. She returned, telling her husband that their plans were firm, that only an anti-discrimination ordinance would prevent what promised to be the largest demonstration in the capital's history. Mrs. Roosevelt urged her husband to act for both moral and political reasons. He agreed but would only go so far. He agreed to have the FEPC prohibit discrimination in defense plants, but he refused to address the issue of segregation in the military, which had been Randolph's original concern.

An analysis of the incomes of Black workers who gained entry into the defense industries compared to those outside them showed that they benefited from higher wages and generally retained their jobs in the early postwar years until 1950. The Fair Employment Practice Committee did not end racial discrimination in employment practices during World War II, but it did have a lasting effect in that era. It opened some doors, as far more of its cases were based on "refusal to hire" than "refusal to upgrade" or "discriminatory working conditions." It helped Blacks enter "industries, firms, and occupations that otherwise might have remained closed to them." The operation of the FEPC supported the idea that "economic rights can be obtained principally by activity in the economic sphere: through education, protest, self-help, and, at times, intimidation." It gained the support of states and governments to eliminate racial discrimination in employment practices.

During its brief period of operation from 1941 to 1946, the FEPC encouraged the formation of other groups with similar goals, such as the Leadership Conference on American Civil Rights, which supported the National Council for a Permanent FEPC. By creating opportunities for Blacks in the defense industry through the opening of good-paying jobs, the FEPC provided a pathway to advancement. By 1950, compared to other men in comparable positions, Black workers who gained jobs in defense made 14% more than their counterparts outside of defense. The proportion of Black individuals in the defense industry did not decline after the war, suggesting that many men had gained entry into crucial new roles.

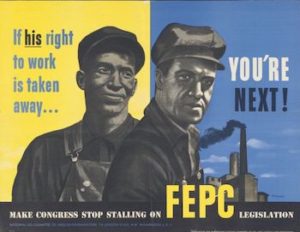

In 1948, President Truman asked Congress to approve a permanent FEPC, anti-lynching legislation, and the abolition of the poll tax in federal elections. A Democratic coalition prevented the legislation from passing. Still operating effectively with one-party systems in their states due to the disenfranchisement of Blacks at the turn of the century, Southern Democrats had influential positions in Congress, controlling chairmanships of important committees, and opposed these measures. In 1950, the House approved a permanent FEPC bill, but Southern senators filibustered, and the bill failed. Congress has never enacted the FEPC into law. But Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Washington successfully enacted and enforced their FEPC laws at the state level.

To become a Financial Management Analyst

To become a Market Research Analyst